Adrienne Skye Roberts is an artist, activist, educator, writer and curator based in Oakland, California. Her practice expertly navigates the spaces between these disciplines exploring issues of class, race, gender, sexuality and gentrification in a variety of media. Her strategies of community engagement and political protest call to mind political actions implemented by groups like ACTUP (Aids Coalition to Unleash Power) and Gran Fury in the early days of the AIDS pandemic. Like many contemporary queer activists, her aim is to fight the oppression of all silenced populations. She is currently an active member of the California Coalition for Women Prisoners. (CCWP), and will present an installation based on this work for Strange Bedfellows.

The title of this new piece, “It is our duty to fight / It is our duty to win / We must love each other and protect each other / We have nothing to loose but our chains,” is based on an Assata Shakur chant that the CCWP says before and after most actions.

Hear audio of the chant below:

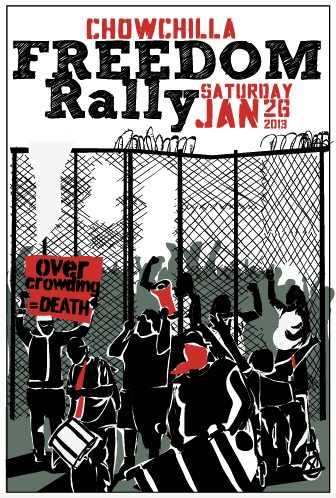

Adrienne collaborated with three fellow coalition members, and prison survivors, on an installation featuring hand painted signs and audio based on interviews and audio from the recent Chowchilla Freedom Rally which they organized together.

Amy Cancelmo: Tell us a little about the project you are working on for “Strange Bedfellows.”

Adrienne Skye Roberts: In this project I collaborate with three prison survivors and fellow members of the California Coalition for Women Prisoners. I interviewed each person and asked them the following questions: How did you survive prison? What do you need to survive now that you are out of prison? And what does a world without mass incarceration look like? These interviews were then edited together into an audio track with additional audio from the Chowchilla Freedom Rally, a mass mobilization to protest the severe overcrowding at the Central California Women’s Facility in Chowchilla, CA in January 2013, of which myself and these three CCWP members helped to organize.

I then pulled specific quotations from each interview and created hand drawn and painted protest signs. The text on these signs are fragmented answers to each of the three questions. They only tell part of the story of each prison survivor (the audio offers more of their stories). Together the collection of signs offer a more emotive and personal side of protest and our collective work against prisons and for the rights of prisoners.

AC: What is your involvement with the California Coalition of Women Prisoners?

ASR: I have been involved with CCWP for three years as a volunteer member. I wear many different hats in this organization. I am part of a visiting team that regularly visits our members who are locked up in the women’s prison in Chowchilla—many of whom are serving life sentences—and I work in the county jail as part of Fired Up! a weekly self-empowerment group where I also do legal advocacy and support for people who are pre-trial and their family members. As an organization we are involved in various campaigns, protests and coalition work for prisoners rights—these days we are focusing our energy on the overcrowding in the California state prisons, the abominable medical care and putting pressure on the Department of Corrections to release people through the various programs they have designed but haven’t implemented. We also do a lot of public events educating people about the prison system and I do a lot of unglamorous but necessary administrative work!

AC: How does political organizing interact with your art practice?

ASR: This is something I think I will forever be figuring out. I believe in artists as agents for social change and in that sense, there is very little distinction between my political organizing and my art practice. The artwork I do emerges directly from the political context I work in and communities I am a part of. Organizing and art making comes from the same place for me emotionally—the desire to effect systemic change, to build deep connections with people. When I was working in tenants rights my curatorial and writing practice focused on local responses to gentrification and redevelopment and so, this project is a natural extension of my organizing with CCWP.

In many ways organizing and art making are also very separate in my life. I don’t have any illusions about the limitations of art making. In other words, I will never be satisfied only making art about the issues I care about because at the end of the day no matter how successful a gallery show is or a poster series, art will not address the very tangible and basic needs of someone getting out of prison or a family who is facing eviction. Art has the ability to communicate what a protest or meeting may not be able to, it can shift consciousness and educate and lift up certain stories and voices and we need that—and we also need political pressure, policy change, direct services, funding and more support. Lately I’ve been trying to figure out how I can make work that functions both to shift consciousness and educate and also be used for long-term organizing goals.

AC: I’m really interested in how CCWP has recently used the phrase “Overcrowding = Death,” a nod perhaps to ActUp’s slogan “Silence = Death.” Do you see a connection between AIDS organizing, and/ or queer radical politics in general with prisoners rights?

ASR: It’s funny I never thought about the ACT UP slogan—even though I am super gay! “Overcrowding = Death” was part of the messaging we developed for the Chowchilla Freedom Rally which happened in January of this year and it is just the most accurate description of what is currently happening in California state prisons. Central California Women’s Facility is currently the most overcrowded prison in the state and as a result of these conditions the already horrific medical care is getting even worse and people’s lives are being threatened and three people have died in this prison alone.

CCWP was founded in a similar political moment back in 1995 when people incarcerated in this same prison filed a lawsuit against the state of California because the medical care was so bad it violated their 8th amendment rights. Some of the founders of CCWP on the inside were themselves HIV+ or living with AIDS—so there is a very obvious connection between these issues.

But I think there are less obvious connections, too. Prisons rely on a culture of silence—they are built on the silencing of certain people, the removal of those people from our communities, the silencing of dissent and the expectation that our voices will not be heard. In both the crisis of prisons and the AIDS crisis, silence becomes an instrument of a system that says some lives are more valuable than others. So, the organizing around both relies on breaking this silence.

I often say that organizing against prisons and for prisoner rights is like organizing in the belly of the beast. Prisons are places that make visible intersecting oppressions—racism, classism, transphobia, and so on. Being queer has made me aware of systems of power and privilege in relation to gender and sexuality and I feel fortunate to be given so many opportunities to push my consciousness beyond what is prescribed as a mainstream LGBTQ political agenda. Organizing from my queerness and my feminist politics, for that matter, means acknowledging this intersectionality and critiquing systems of power: patriarchy, white supremacy, capitalism—all of which are the foundations of mass imprisonment. Prison abolition, like queerness, relies on imagining an entirely different world—and then not waiting for that world to be given to us, but working together to make it a reality.

AC: Tell me a little about your collaborators.

ASR: I collaborated with three people for this project—all of whom are survivors of prison and members of CCWP. I work with all of them in various capacities and as it goes in this work, they are family. Windy Click was released from prison in September 2012 after serving 17 years. She has been a member of CCWP for 10 years and an organizer inside and facilitator of many peer led groups. Windy was a core organizer of the Chowchilla Freedom Rally. Mary Campbell survived 5 years at CCWF (Central California Women’s Facility) and she is a member of the self-empowerment group at the county jail and we facilitate this group together. Misty Rojo is the current Program Coordinator at CCWP. She survived 10 years at CCWF and was a board member of the organization Justice NOW during her incarceration.

Hear an excerpt from Windy’s interview below:

Hear an excerpt from Misty’s interview below:

AC: Are you involved in other political causes?

ASR: Well, there are only so many hours in a day! Right now my energy is very focused on anti-prison organizing and supporting people inside. I have a background in housing and tenants rights and feminist youth organizing. I really believe that our movements are intersectional and related to each other—for example, people with unstable housing are more vulnerable to arrest, so organizing for housing justice has a direct impact on keeping people out of jails and prisons—the same could be said about immigration and education.

AC: Do you differentiate queer activism from other forms of social or political interventions?

ASR: I don’t personally differentiate or define my activism as queer or not—queerness is one of the many frameworks of my organizing and life. There certainly are actions that are more obvious queer like protesting San Francisco PRIDE’s refusal to name Bradley Manning as the Community Grand Marshal or protesting the Human Rights Coalition for their support of transphobic legislation. And there is a strong tendency to divide ourselves and compartmentalize our movements. But I think it is dangerous to develop political agendas that are only queer or one-dimensional. Our lives are more complicated than that and the injustices enacted on us are multi-faceted. We need complex approaches to address these problems and we need movements that allow for every aspect of ourselves to be acknowledged.

Speaking personally, I have learned and grown and felt more than I thought was possible in movements where I am acting in solidarity with people whose lived realities and experiences of oppression are different than my own and I am so grateful for this.

AC: What role do you see art playing in activism?

ASR: I ask so many artist-organizers this same question myself because I am desperate to know how people reconcile these things! I am indebted to Jeff Chang and Favianna Rodriguez who introduced me to the idea of cultural organizing; that culture and politics do not exist in a vacuum but actually influence each other. We need cultural organizers for so many reasons. Art provides another access point for many people who may not be inclined to attend a political meeting. Artists are storytellers and stories often speak to people more than statistics or a legislative analysis. Art facilitates healing. I also think artists are well trained in “thinking outside the box,” pulling resources and visioning and we need that energy in our political movements, we need artists to be at the table when decisions are made.

For this project there are overlapping goals—to tell the stories of three prison survivors in an effort to raise awareness about this reality, to create an audio track that can be used for various re-entry projects and funding for CCWP and to emphasize some spaciousness and visioning in this work. My art making isn’t necessarily a “break” from activism because the source is still the same but it feels so different.

AC: Do you think there is something inherently queer about collaboration?

ASR: In my definition of queer, yes. Queerness, as a critique of systems of power, speaks back to the capitalist fantasy of the individualist and everything we are taught about isolating ourselves in our work or our nuclear family or when we need help the most. This is opposite of what so many of us—queers, radical thinkers, many marginalized communities—know to be true: that we rely on each other, that we need each other every step of the way for our survival, our resistance and our joy. This is my experience as an organizer, as a queer person, and as an artist. And it isn’t always easy—collectives are hard work, building community takes time and collaboration requires a lot of flexibility and humility but I wouldn’t want to live any other way.

Learn more about the California Coalition of Women Prisoners